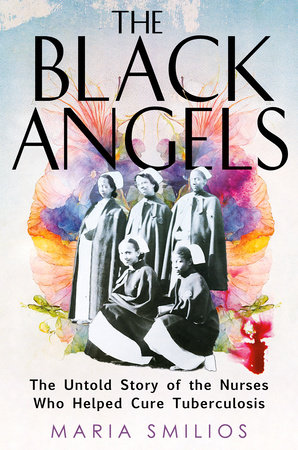

Review of “The Black Angels: The Untold Story of the Nurses Who Helped Cure Tuberculosis,” by Maria Smilios

By Theresa Brown, PhD, RN

This review was first published in the American Journal of Nursing, February 2024. Reprinted by permission.

It’s hard to believe now, but tuberculosis used to be an international scourge. In the forty years between the discovery of the drug that cured the disease (isoniazid) and that drug’s actual clinical use—from 1912-1952—60 million people died of the disease. (p. 345). Maria Smilios’s The Black Angels: The Untold Story of the Nurses Who Helped Cure Tuberculosis reveals the role that Black nurses specifically, working at the Sea View Sanitorium on Staten Island, played in finding the cure for tuberculosis. Those heroic Black nurses did work that white nurses were unwilling to do, all while navigating the racism of the time, which was in some ways no less virulent than TB itself.

The book begins by telling the story of one of those Black Angels: Edna Sutton. Edna grew up in Savannah, Georgia, her life circumscribed by Jim Crow racism that made her dream of working as a nurse impossible to achieve. She had trained to be a nurse but couldn’t get a job due to discrimination against Black nurses and ended up doing office work instead. However, in the summer of 1929, one of Edna’s former nursing instructors told her that Sea View Sanitorium in New York city was hiring “colored” nurses, and even paying the education costs of those who needed additional training. Edna took time to consider the opportunity, and after being accepted at Sea View, left Savanah for New York City and a new life as a paid professional nurse.

The reason Sea View decided to hire Black nurses had to do with the impossibility of keeping white nurses on staff. Sea View was a public sanitorium for tuberculosis patients; many of the patients were immigrants, and all were poor. More important to the nurses, the work was dangerous since nurses could become infected with, and die from, tuberculosis. Sea View experienced a mass exodus of white nurses beginning in spring, 1929. No one knew exactly why the white nurses left, but Smilios surmises that, “working white woman [sic] had plenty of options for jobs that wouldn’t kill them: salesclerks, cashiers, stenographers, secretaries, librarians, and telephone operators.” (p. 4)

Enter the Black Angels, for whom Sea View was an opportunity to do the work they felt called to do and were prohibited from doing in the south, and also in most of the hospitals in New York City. The work was not just dangerous, but also physically and emotionally challenging due to the rigors of the disease:

“Edna saw how tuberculosis annihilated the body in fantastic ways…it dug deep, devouring the spines of the children and mashing up the brains of aspiring singers. In the immigrant stonemason, it had pulverized his lungs, nearly liquefying them.”

The Black Angels, p. 60-61

The Black nurses were also often short-staffed, meaning there was always more misery on the wards than they could adequately minister to.

When a cure for tuberculosis was discovered, Dr. Edward Robitzek, who led those efforts at Sea View, credited the Black nurses for the successful trials of isoniazid, saying they “ran the wards.” (p. 252) According to Smilios, the nurses also, “Knew how the disease ebbed and flowed, how it cloyed, then let go; they knew its moods and how vicious it became, its arrogance and disregard for human life.” (p. 319) Their knowledge and clinical experience made the Black Angels uniquely qualified to manage “a trial of this magnitude.” (p. 319)

Sea View was eventually closed as more and more patients recovered and went home, and over the same time period more nursing programs and hospitals across the country admitted Black nurses. The American Nurses Association, which had excluded Black nurses for decades, finally welcomed them, leading to the dissolution of the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses in 1951, because they were now “American nurses, not ‘Negro nurses.’” (p. 312-14)

Black Angels is an excellent read for Black History Month, and really anytime, because it tracks the stubbornness and destruction of tuberculosis in the body along with racism in the body politic. The Black nurses at Sea View prevailed against a terrible disease, and “Reserved for Whites” signs in the dining room at Sea View, the overt hostility of their White neighbors on Staten Island, and a rigid and racist nursing supervisor. The systemic racism inflicted on the nurses was pervasive and personal. I would never have understood that racism as akin to an unforgiving wasting disease without Smilios’s book, which shows heroism and goodness prevailing anyway, a testament to the integrity and commitment of Sea View’s Black nurses.

An online exhibit about Sea View Hospital is available from the Staten Island Museum.

About the Author

Theresa Brown, PhD, BSN, RN, is a nurse and writer who lives in Pittsburgh. Her third book–Healing: When a Nurse Becomes a Patient–will be available April 2022. It explores her diagnosis of and treatment for breast cancer in the context of her own nursing work. Her book, The Shift: One Nurse, Twelve Hours, Four Patients’ Lives, was a New York Times Bestseller.

Theresa has been a frequent contributor to the New York Times and her writing has appeared on CNN.com, and in The American Journal of Nursing, The Journal of the American Medical Association, and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Theresa has been a guest on MSNBC Live and NPR’s Fresh Air. Critical Care: A New Nurse Faces Death, Life, and Everything in Between is her first book. It chronicles her initial year of nursing and has been adopted as a textbook in Schools of Nursing across the country.

Theresa’s BSN is from the University of Pittsburgh, and during what she calls her past life she received a PhD in English from the University of Chicago. She lectures nationally and internationally on issues related to nursing, health care, and end of life. Becoming a mom led Theresa to leave academia and pursue nursing. It is a career change she has never regretted.