When Dr. Michael Grady retired, he didn’t stop saving lives—he volunteered to help in Haiti, Gaza, Ukraine and beyond.

By Elizabeth Austin Levoy, Senior Communications Specialist

Photos by International Medical Corps

First published September 30, 2024 by International Medical Corps

As we reflect on International Medical Corps’ 40-year history, we are highlighting some of the courageous volunteers and staff members who have dedicated their lives over the years to helping others. This profile of Dr. Michael Grady is the fourth in that series. We previously have profiled two other volunteers, Dr. Mike Karch and Dr. Chuck Wright, and staff member Dr. Dayan Woldemichael.

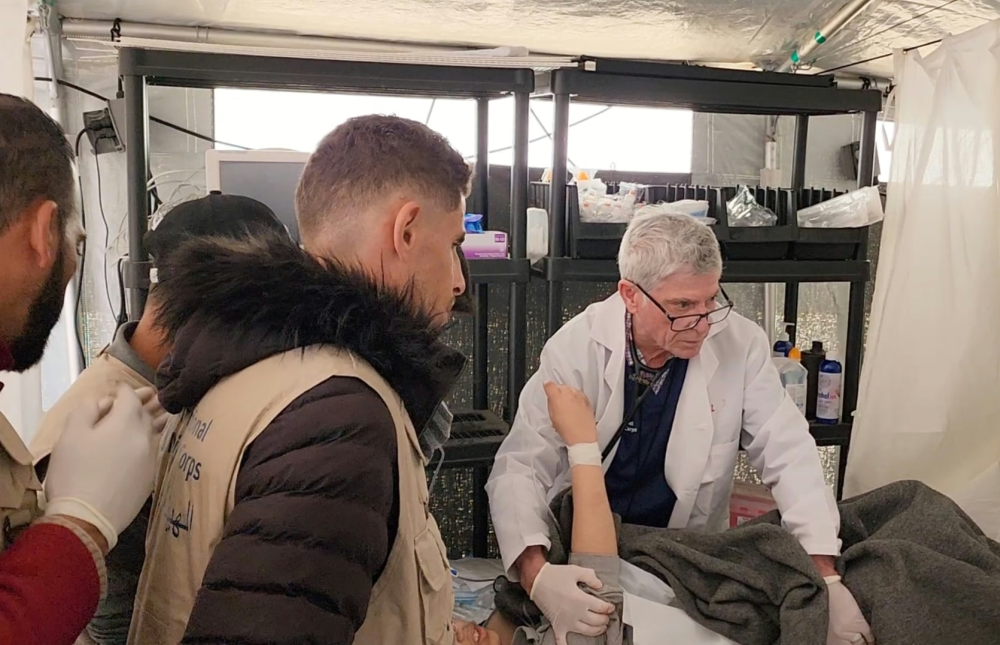

“We realized early on that we were probably going to be one of the last standing hospitals in southern Gaza,” says Dr. Michael Grady, an International Medical Corps volunteer who deployed to one of our field hospitals in Gaza for six weeks. “And at a field hospital, where you don’t have CAT scanners or MRI machines, you have to depend on basic diagnostic skills when you examine a patient—listening to their heart and their lungs, and putting your hand on their shoulder while you listen to them talk, learning about their symptoms through a translator.”

He pauses here, takes a moment and then adds, “You know, without sounding sort of hackneyed, when you give back, you always get more than you give. I find that to be true.”

For his dedication and bravery as a volunteer, Dr. Grady will be honored with International Medical Corps’ Henry H. Hood Distinguished Service Award at the 2024 Annual Awards Celebration.

Discovering his purpose in an operating room

Michael Grady grew up in Massachusetts, “in a small town halfway between Plymouth and Boston,” he explains. “When I was in high school, I developed a pain in my abdomen, which turned out to be appendicitis. When my appendix was removed, I became completely fascinated with hospitals, operating rooms and surgeons. Fortunately, the doctor who took out my appendix ran a boys’ camp on an island 2 miles off the coast of northern Maine.

“I started going to the camp, and this doctor took me under his wing. I actually wound up living with him through my last year of high school, and I would follow him at night to the operating room, where I learned surgical anatomy, how to tie knots and how to manipulate surgical instruments. And then, on weekends, I would volunteer in this little emergency room. I became fascinated with medicine and the care of patients, and I just knew, even as a senior in high school, that this was what I wanted to do with my life.”

After high school, he earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of Massachusetts in Boston. He then went to medical school in Maine, followed by a rotating internship, and then a four-year residency in obstetrics and gynecology (OB/GYN) in Detroit. After residency, Dr. Grady moved to the Atlanta area, where he founded an OB/GYN practice.

“I started a small, one-provider practice to fulfill a public-health service obligation,” Dr. Grady explains. The US Public Health Service paid for his medical school tuition and expenses. In exchange, he was obligated to serve in a medically underserved area for four years.

“There was a time when I was delivering 60 babies a month, without other doctors in the practice to cover shifts. It could be overwhelming, but it was rewarding, too. Eventually, it grew to become a much larger practice with five or six doctors and six or seven midwives.”

After his obligation ended, Dr. Grady continued working in the Atlanta area due to the overwhelming need of the patient population. He became Chief of Staff at his community hospital, eventually serving on the board of directors, ultimately as Board Chairman. After more than 20 years at the hospital, he decided to retire following a hand injury.

Dr. Grady and his wife, Kristen—who are the proud parents of five children and grandparents to seven, with another on the way in February—moved to Asheville, North Carolina, but that didn’t mean he stopped practicing medicine.

Volunteering amid disaster and disease

“After my retirement, I became involved with a nonprofit organization in Haiti, helping to run a remote clinic in the mountains, which continues to operate to this day,” he explains. Also a flight instructor, Dr. Grady even helped fly X-ray equipment for the clinic into Haiti.

“I’ve been to Haiti close to 30 times. I also deployed there following the earthquake in 2010, and I spent a couple of weeks in Port au Prince running an aid station.”

After volunteering in Haiti, his humanitarian work continued—he worked with another nonprofit in West Africa during the Ebola epidemic, becoming the clinical lead at an Ebola treatment center in Sierra Leone, where he and his team often saw more than 100 patients per day.

“During that time, I was asked to open an Ebola screening center at a large maternity hospital in Freetown, because early labor symptoms can be the same as Ebola symptoms,” he explains. “Due to this confusion, some of these patients were left to die in the parking lot while they were in labor, making Ebola screening a vital issue. I developed a protocol to help diagnose and manage these patients, some of whom were both in labor and had Ebola.”

Training first responders in Ukraine

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, Dr. Grady looked for an organization where he could volunteer. A close friend introduced him to International Medical Corps. Impressed by our emphasis on training and security, Dr. Grady decided to deploy with our team to Ukraine.

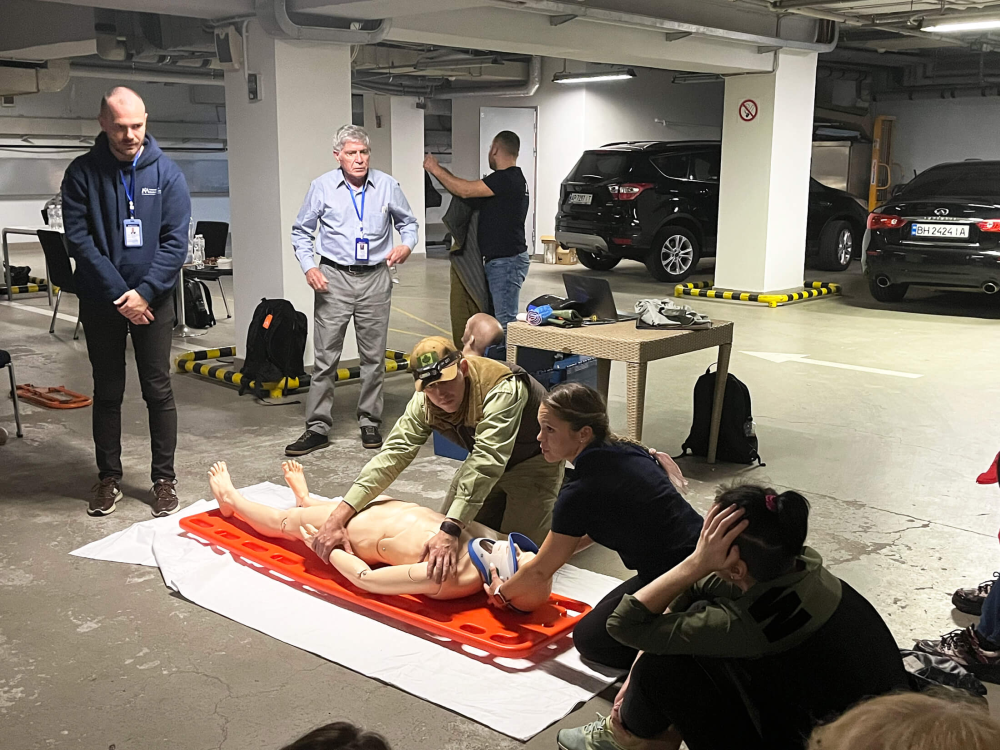

“Ukraine was different than other humanitarian work that I’ve done,” Dr. Grady explains. “It was more about teaching. The people who had been providing emergency care before the war had been recruited to the front lines, so it left huge gaps in their healthcare system.”

Along with several volunteers and staff members, Dr. Grady provided comprehensive emergency- and trauma-care training to Ukrainian healthcare workers, public safety workers and other community leaders. The team also employed a “train the trainers” approach.

“We identified teachers among our students, and those teachers were soon standing next to us, teaching the same thing that we were teaching,” he remembers. “And the beauty of that is they didn’t need translators. And so, suddenly, we had a cohort of former students who were excellent teachers and could speak the language. There was a cascading effect of our knowledge and ability to transmit this knowledge to students. And now, all throughout Ukraine, people are teaching these lifesaving courses.”

Dr. Grady spent several weeks during multiple trips to Ukraine in 2022 and 2023, often very close to the front lines, where his team would sometimes be forced to conduct training in bomb shelters during air-raid alerts. Then, in October 2023, war erupted in the Middle East.

Deploying to help civilians in Gaza

Soon after, International Medical Corps deployed a field hospital to Gaza to provide urgently needed healthcare to civilians affected by the war. Despite the dangers, Dr. Grady knew he had to go and help—he deployed to International Medical Corps’ initial field hospital in southern Gaza and was there for more than a month.

“Gaza was a very, very intense place to work,” he says. “Initially, we were ramping up and expecting a few dozen patients a day. And suddenly, we had 100 patients a day. And then we had 600 patients a day. We were expecting a couple of cases in the emergency department each day. Suddenly, we had 30, 40 and then 50 patients who were critically injured, coming in one at a time from an explosion.”

The sound of drones, the smell of smoke and the suffocating heat were ever present, as was the wailing of family members and patients.

“There are several patients whose memory I carry with me,” he says. “One is a seven-year-old girl who had a piece of shrapnel that entered her face just below her right eye. She came [to the field hospital] in the afternoon and went into surgery the following day. I remember her father was so upset. He was distraught. I remember taking him aside and talking to him, telling him that I’m a father and I realize how upsetting this is. And I reassured him that we were going to take care of his daughter. Fortunately, we had a person on our team who had been trained as an ear, nose and throat doctor, and so he was able to help the team remove this giant hunk of metal that was embedded in her face.”

Dr. Grady is proud of and committed to his family. When one of his granddaughters needed a liver transplant at age one, he donated half of his liver to her—she is thriving, and he is grateful.

During his deployment in Gaza, Dr. Grady spoke with CBS News, which was reporting on conditions in the war zone. When Dr. Grady returned from Gaza, he spoke with CNN host Sara Sidner about humanitarian conditions and helping patients in southern Gaza.

Reflecting on his time in Gaza and his work with International Medical Corps, Dr. Grady is grateful for the opportunity to help and bring hope to the people we serve.

“I think when patients came there, they saw compassion,” Dr. Grady says. “They saw hope because we had hope. I think that makes a huge difference. And for the staff and volunteers, people feel proud to be part of the team. I don’t travel with other organizations now. If I’m going someplace to help, it’s with International Medical Corps.”

Related Articles

When Ukrainian Refugees in Poland Needed Help, We Were There

Just days after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, International Medical Corps launched a response in Poland to help Ukrainian refugees there. Here’s what we’ve done since then.

Photo Essay: After Helene, Health Workers Are a Lifeline for the Displaced

The team from International Medical Corps is delivering crucial care for the mind and body while the people of Asheville rebuild and recover.

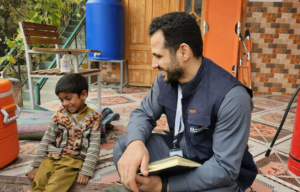

Ahmed Kassas: Transforming Lives Across Countries

Afghanistan Country Director Ahmed Kassas is a man on a mission to transform the lives of others: the people in the communities where International Medical Corps work, as well as his colleagues.