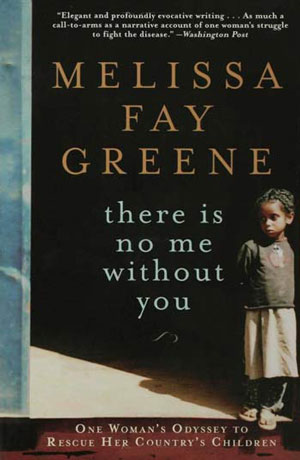

There Is No Me Without You

THERE IS NO ME WITHOUT YOU is the story of Mrs. Haregewoin Teferra, a middle-class Ethiopian widow whose home became a refuge for hundreds of AIDS orphans, and about a few remarkable children who moved through her life.

-----

The data had hit me acutely for the first time one Sunday summer morning in Atlanta in 2000.

I was lounging by the sunny bay window, finishing my coffee, idly screwing in a pierced earring, as the Sunday New York Times spread its dark news across the kitchen table. I read, for the first time, the United Nation's description of Africa as "a continent of orphans." The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) had killed more than twenty-one million people, including four million children.

More than thirteen million children had been orphaned, twelve million of them in sub-Saharan Africa. Twenty-five percent of those lived in two countries: Nigeria and Ethiopia. In Ethiopia, 11 percent of all children were orphans.

And there was more.

UNAIDS (the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS) predicted that, between 2000 and 2020, sixty-eight million more people were going to die of AIDS (a disease of which few Westerners had died since the creation of antiretroviral [ARV] drug therapies in the late 1990s).

By 2010, between twenty-five million and fifty million African children, from newborn to age fifteen, would be orphans.

In a dozen countries, up to a quarter of the nation's children would be orphans.

The numbers were completely ridiculous.

Twelve million, fourteen million, eighteen million -- how could numbers so high be answers to anything other than "How many stars are in the universe?" or "How many light-years from the Milky Way is the Virgo Supercluster?"

-----

In the summer of 2000, my husband, Don Samuel, a defense attorney, and I had been married twenty-one years. We had two daughters and three sons, four by birth and the youngest by adoption: Molly had been born in 1981; Seth, 1984; Lee, 1988; Lily, 1992; and Jesse, 1995. In our forties, we were being driven cheerfully insane. We staggered through the middle-class blizzard of permission slips, soccer cleats, library books, musical instruments, dental appointments, science-fair projects, and college applications. In my pockets at night, I found things like somebody's chewed gum, or a small earring in the shape of a dolphin, or a one-armed Spider-Man action figure (or, on a different night, Spider-Man's missing arm). Once I was asked to empty out my purse at airport security and there was a life-size plastic banana at the bottom of it. I actually knew what the banana was doing there, but -- since it didn't pose an immediate threat -- I was waved on through without being asked to explain. Our front yard looked like a bicycle depot. There were bald spots in the grass from the badminton games.

On that summer morning, the children and their sleepover friends were yelling from room to room, and dragging sleeping bags and beach towels all over the house, and looking for small change so they could purchase Popsicles at the pool snack-bar. Someone got in the car and began helpfully honking the horn to urge the parents to hurry, despite the parents' repeated clarification that the pool outing would happen in a little while. That was the summer that five-year-old Jesse, adopted the previous fall from a Bulgarian orphanage, learned to swim in a single afternoon. When we asked, "How did you learn to swim so quickly?" he replied, "The shark that lives in the deep end taught me."

But suddenly here was this world beyond our house: twelve million orphans today. Twenty-five million orphans tomorrow. And those were just the numbers of AIDS orphans; if you added in the orphans from malaria and TB, you hit thirty-six million sub-Saharan orphans, and those numbers didn't include children deprived of the adults in their lives by war and famine.

-----

Human beings are not wired to absorb twelve million or eighteen million or twenty-five million bits of information; our protohuman ancestors never had to contemplate more than about ten or twenty of anything. For a person who is not a mathematician, epidemiologist, demographer, geographer, social scientist, medical anthropologist, or economist -- for a person, say, who barely knows anyone with one of those jobs (although, living two miles from the Centers for Disease Control [CDC] in Atlanta, I do enjoy carpooling to kids' soccer practices with the occasional epidemiologist), numbers with so many zeros are hard to fathom. Presumably you can make a variety of calculations and graphs with numbers like eleven million and twenty-five million, but hats off to anyone who can begin to imagine what this really looks like, what this means.

Who was going to raise twelve million children? That's what I suddenly wanted to know. There were days that Donny and I thought we'd be driven insane by five children.

Who was teaching twelve million children how to swim? Who was signing twelve million permission slips for school field trips? Who packed twelve million school lunches? Who cheered at twelve million soccer games? (That sounded like our weekends.) Who was going to buy twelve million pairs of sneakers that light up when you jump? Backpacks? Toothbrushes? Twelve million pairs of socks? Who will tell twelve million bedtime stories? Who will quiz twelve million children on Thursday nights for their Friday-morning spelling tests? Twelve million trips to the dentist? Twelve million birthday parties?

Who will wake in the night in response to eighteen million nightmares?

Who will offer grief counseling to twelve, fifteen, eighteen, thirty-six million children? Who will help them avoid lives of servitude or prostitution? Who will pass on to them the traditions of culture and religion, of history and government, of craft and profession? Who will help them grow up, choose the right person to marry, find work, and learn to parent their own children?

Well, as it turns out, no one. Or very few. There aren't enough adults to go around. Although in the Western industrialized states HIV/AIDS has become a chronic condition rather than a death sentence, in Africa a generation of parents, teachers, principals, physicians, nurses, professors, spiritual leaders, musicians, poets, bureaucrats, coaches, farmers, bankers, and business owners are being erased.

-----

The ridiculous numbers wash over most of us. This is happening in our time? We, who have read the histories of the Armenian genocide and of the Holocaust and of Stalin's Gulag, who have lived in the epoch of the killings in Cambodia, Bosnia, and Rwanda, find ourselves once again safely tucked away. We may feel a vague sad tug of common cause with human misery on the far side of the Tropic of Cancer, but we are disconnected from it by a thousand degrees of space and time. This is true even in the hardest-hit countries, because even in the highest-prevalence countries of Asia and Africa, there are comfortable citizens -- including elected leaders -- keeping their hemlines above the rising waters.

The Berlin Wall is down, the Iron Curtain has fallen, but it is as if a pulsating wall of strobe lights, televised celebrities, and amplified music has gone up mid-Atlantic or mid-Mediterranean Sea. It is hard to look past the simulated docudramas, television "newsmagazines," and mock-reality memoirs designed to distract us in a thousand ways while making us feel engaged with true stories. America wrestles with its obesity crisis to such an extent that Americans forget there are worse weight problems on earth than obesity.

A few Westerners smash through. UN special envoy Stephen Lewis is one of these; the bow-tied, globe-trotting, charismatic physician Jonathan Mann, who died in a plane crash off Halifax, was another. Bill and Melinda Gates and former presidents Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton are there.

How can the rest of us -- normal citizens, steering along our paved streets between home and school, work and playground, mall and hardware store, holding open the front door with a foot while maneuvering inside with the mail, the grocery sacks, the purse, a paperback, the children's backpacks -- how can the rest of us break through?

-----

On that Sunday morning, as kids in swimsuits honked from the driveway for me to hurry up, I suddenly wondered, "Can you adopt one of the African AIDS orphans?" The notion of adoption gave me a way in, a way to look behind the big numbers with all the zeros. Before I went to Ethiopia as a journalist, I went as an adoptive parent; Ethiopia was one of the few countries in Africa permitting foreign parents to adopt.

Going to Ethiopia as an adoptive mother turned out to be the best possible introduction to Haregewoin Teferra. Mothers were endangered where she came from, so a mother willing to care for children not hers by birth was praiseworthy indeed.

I wouldn't end up adopting a child from Haregewoin's compound, but I found my way to her through the chain of men and women -- Ethiopians and Americans -- handing orphans one by one out of Ethiopia to adoptive families in the West.

Adoption is not the answer to HIV/AIDS in Africa. Adoption rescues few. Adoption illuminates by example: these few once-loved children -- who lost their parents to preventable diseases -- have been offered a second chance at family life in foreign countries; like young ambassadors, they instruct us. From them, we gain impressions about what their age-mates must be like, the ones living and dying by the millions, without parents, in the cities and villages of Africa. For every orphan turning up in a northern-hemisphere household -- winning the spelling bee, winning the cross-country race, joining the Boy Scouts, learning to rollerblade, playing the trumpet or the violin -- ten thousand African children remain behind alone.

"Adoption is a last resort," I would be told in November 2005 by Haddush Halefom, head of the Children's Commission under Ethiopia's Ministry of Labor, the arbiter of intercountry adoptions, "Historically, close kinship ties in our country meant that there were very few orphans: orphaned children were raised by their extended families. The HIV/AIDS pandemic has destroyed so many of our families that the possibility no longer exists to absorb all our Ethiopian orphans.

"I am deeply respectful of the families who care for our children," he said. "But I am so very interested in any help that can be given to us to keep the children's first parents alive. Adoption is good, but children, naturally, would prefer not to see their parents die."

=====

Order the Book

You can purchase the book, There Is No Me Without You, online at the author's website.

About the Author

Melissa Fay Greene is a regular contributor to The New York Times Magazine and Good Housekeeping. She also writes for The New Yorker, The Atlantic, Readers Digest, Newsweek, Life, The Washington Post, Ms, and Parenting. She has been a frequent guest at CNN and on NPR, and her stories have been featured on Good Morning, America, The Today Show, Primetime, and 20/20. She is married to Donald F. Samuel, a criminal defense attorney, live in Atlanta, and have nine children, one son-in-law, two daughters-in-law, one grandson and one granddaughter. You can learn more about Ms. Greene, including her other award-winning books, on her website.

About Angels in Medicine

Angels in Medicine is a volunteer site dedicated to the humanitarians, heroes, angels, and bodhisattvas of medicine. The site features physicians, nurses, physician assistants and other healthcare workers and volunteers who reach people without the resources or opportunities for quality care, such as teens, the poor, the incarcerated, the elderly, or those living in poor or war-torn regions. Read their stories at www.medangel.org.